**We read each and every book and watch each and every movie we review thoroughly and only give top place to those that deserve it; we offer honest reviews. We are independently owned and the opinions expressed in our posts are our own. We do receive compensation from the links found in this article.**

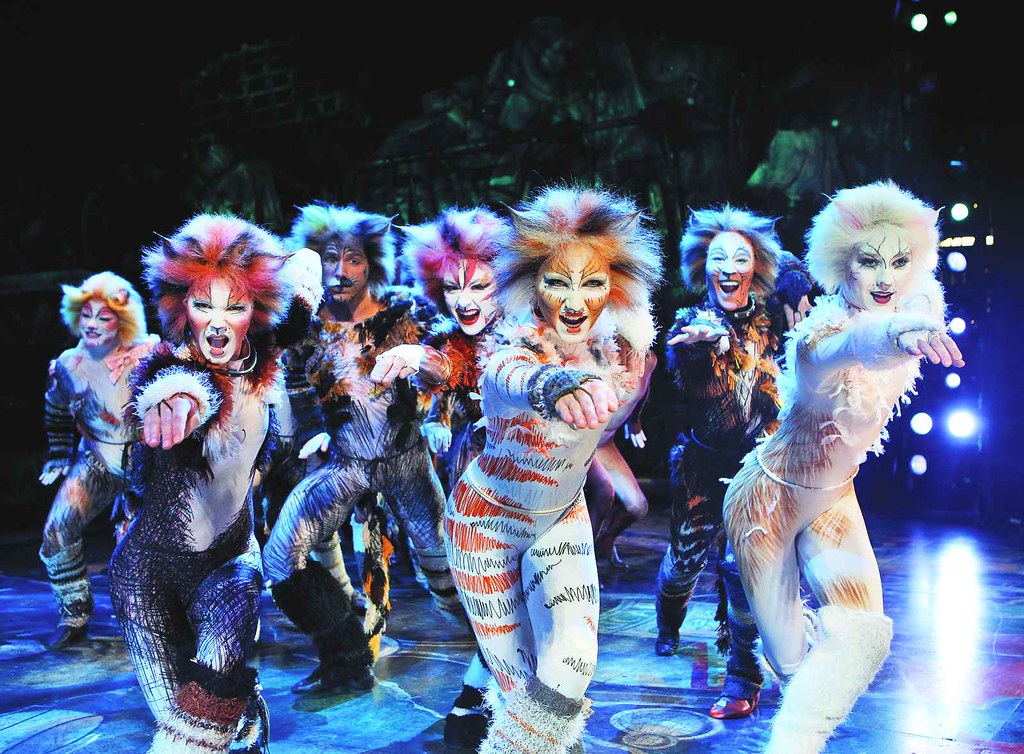

Andrew Loyd Webber’s Cats is the highest-grossing musical production of all time, and the fourth longest-running Broadway production. It’s a musical beloved by many, including me: since before I could even speak, I would sit in the living room and watch the 1998 film adaptation on repeat.

Cats has received some criticism for its apparent lack of a plot, and the plot is admittedly vague. The “story,” such that it is, allows the audience to witness the night of the Jellicle Ball, with musical introductions to each major character present. At the end of the Ball, Old Deuteronomy, the clan patriarch, makes the “Jellicle Choice” and decides which cat will ascend to the “Heavyside Layer” to begin a new life. My child’s mind took this to be a sort of cat heaven, and while critics of the original Broadway production were unsatisfied with the plot, it was good enough for me, and continues to be enough for many other Cats lovers.

Why is the plot of Cats so vague and simplistic? Well, probably because all of the songs in it come directly from T.S Eliot poems, and it’s not exactly easy to make a cohesive plot out of a collection of separate poems.

T.S Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats

Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats is the source of nearly all the lyrics in Webber’s musical. Eliot wrote the whimsical feline poems in the 1930s and sent them to his godchildren, signed with the name “Old Possum.” In 1939 he compiled these poems and had them published by Faber and Faber in the book Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats.

The first poem in the book is “The Naming of Cats,” a now-famous work that discusses the three different names that cats must have, while “The Song of the Jellicles” describes a type of cat, and the final poem of the original edition, “The Ad-Dressing of Cats” tells humans how they should approach their feline acquaintances.

Each of the other poems in the book introduce the reader to different cats, their personalities, and their jobs.

Andrew Loyd Webber’s Adaptation: Cats

Webber’s musical adaptation Cats is famous worldwide. Really, there are as many different adaptations of Eliot’s book as there are individual performances of Webber’s musical, and each one has its own unique qualities and peculiarities. For the sake of keeping things simple, when I’m talking about the musical Cats, I’ll be talking about the 1998 filmed performance, which pretty much anyone can get access to if they want to watch it.

Structure

The musical gets its loose plot from the three poems in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats that aren’t about individual cats: “The Naming of Cats,” “The Song of the Jellicles,” and “The Ad-Dressing of Cats.” Just as they appear in the book, these form the beginning, middle, and conclusion of the play. “The Song of the Jellicles,” which tells of a Jellicle Ball, is the obvious inspiration for the setting of the musical, though the Heavyside Layer and the Jellicle Choice appear to be Webber’s own invention.

Almost all of the poems in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats are included in Webber’s musical, and in almost the same order as the adapted songs. A few songs, like “Bustopher Jones,” get moved earlier in the play than they appeared in the book, but by far the most major order shift occurs with “Mr. Mistoffelees” and “Macavity: The Mystery Cat.” While everything for these two poems gets plucked out of the middle, flipped (in the book Macavity comes before Mistoffelees), and moved nearer the end. If you compare the 1998 film to the book, you’ll see that this makes sense. It gives the musical a climax and resolution near the end, which Eliot’s collection of separate poems didn’t need.

What’s Missing?

Like I said, almost all of the poems from Eliot’s book are included. So, what got scrapped for the musical, and why?

In Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, nestled between the poems about Jennanydots and Rum Tum Tugger, is the poem “Growltiger’s Last Stand,” which tells of the demise of the rough and rowdy Growltiger, the “Terror of the Thames.” The song was actually included in earlier performances of the musical but stirred up controversy because it includes a racial slur directed at the Chinese. For a while, the song was still performed and the slur altered to “Siamese,” but many still complained of the exaggerated and offensive Chinese accents the white actors in such productions would don when playing the Siamese cats. By 1998 the song wasn’t commonly performed anymore. That, coupled with the age of John Mills, who played the part of Gus that typically got double-cast with Growltiger, ensured that the song didn’t appear in the 1998 film.

One other poem that appears in all but the very earliest editions of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats and gets left out of the production of the musical is found at the very end of the book, “Cat Morgan Introduces Himself.” This poem is a tribute to Eliot’s friend and publisher, T.E. Faber, and the family Morgan. While Weber himself sang a song adaptation of the poem in some of the early performances, it never made it into the musical proper.

What’s New, Pussycat?

Aside from some orchestral arrangements and songs from Weber that establish vague plot and setting, there are a couple of songs in Cats that aren’t based on any poems you’ll find in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. In fact, the most famous song from the musical, “Memory,” doesn’t have anything to do with Old Possum at all! The lyrics of “Memory” are heavily based on a lovely, melancholic Eliot poem called “Rhapsody on a Windy Night.”

Grizabella, the memorable character who sings the song, doesn’t appear in any published poem, either. Eliot had written “Grizabella the Glamour Cat,” but it was ultimately rejected from Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats because it was considered too sad for children. After Eliot’s death, his widow Valerie Eliot gave the poem to Weber, and now the formerly unpublished feline is famous.

The Good, the Bad, and the Sleep Paralysis Demons of Cats (2019)

Alright, its common knowledge that Cats (2019) was a CGI nightmare, so I’m not going to harp on that much. Suffice to say, it’s surprisingly much worse to see in motion than any still picture can do justice. Instead of talking about visuals, I’m going to look at how the changes made from the adapted texts or “source” (both Cats (1998) and Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats) impacts the viewer.

The Good

The shift to film

One of the big changes in how Cats (2019) is presented is a result of it being a film, rather than a filmed stage musical. While Cats (1998) was performed without an audience, it was filmed with the intention of showing a home audience what a live performance would be like. Munkastrap still addresses the imagined audience, pointing to the “man over there, with a look of surprise” who is presumably sitting just beyond the stage. “The Ad-dressing of Cats,” which ends the performance, is clearly Deuteronomy addressing a human audience that has been allowed to observe the Jellicle Ball.

Cats (2019), on the other hand, takes place in its own self-contained world, where the audience is absent (well… mostly, but we’ll get to that). The film has to work harder to get its exposition across, so Victoria becomes a vehicle for the audience’s introduction to the Jellicle Cats and the Jellicle Ball. Since Victoria is traditionally a major dancing role in Weber’s musical, but doesn’t have a dedicated song, this was a great choice. Victoria’s role as outsider entering the clan also allows Weber’s vague plot to be made more explicit, which is laudable. All in all, making Victoria the main character was a great way to adapt a musical intended for a live audience into a film.

Character development

As a dedicated fan of Weber’s musical version of Cats, I have some mixed feelings about the character development in Cats (2019). Mistoffelees starts the film as an earnest but skittish young cat, not yet confident in his magical abilities. It’s through Victoria’s belief in him, everyone’s desperation to get Deuteronomy back, and the support of all of the other cats that he’s able to actually conjure Deuteronomy. His success gives him a newfound confidence, and the pizazz that the 1998 Mistoffelees has from the start of the musical. Overall, it’s a wonderful message about how the love and support of others can lead to great deeds and personal growth, and a tone shift that fits well with the original Eliot poem.

Music

A good number of the songs in Cats (2019) were well-done adaptations of the Weber musical. In particular, the more “serious” songs (like “Jellicle Songs for Jellicle Cats,” “The Naming of Cats,” and the songs associated with Old Deuteronomy, Gus the Theater Cat, ang Grizabella) are fantastic. Victoria’s song “Beautiful Ghosts” (written by Taylor Swift, rather than Eliot) is also lovely, and hits all the right notes of hope in the face of loss.

The Bad

The worst parts of Cats (2019), aside from the terrifying visuals, are the characterizations of at least half of the main cats, whether it’s a result of how their song was adapted or how the plot was specified.

Macavity

Macavity’s song is musically decent in the new film, but adding specificity to the plot did the characters no favors. In the 1998 musical, Macavity was a vague, threatening presence hanging over the Jellicle Ball. The other characters occasionally think they’ve seen or heard him and scatter, but he doesn’t actually appear until nearly three-quarters of the way through the musical. When he finally does appear in person, he does the worst thing possible, and kidnaps Deuteronomy, only to return in disguise as the patriarch of the clan for a surprise attack. Macavity’s motivation and what’s actually become of Deuteronomy is vague enough to be threatening, and Macavity disguised with a Deuteronomy mask is downright uncanny.

The Macavity of Cats (2019) loses all of the mystery that makes him frightening in an effort to make every point of the plot clear. He kidnaps not only Deuteronomy, but all of the cats competing to be chosen for the Heavyside Layer, in an effort to be the last contestant and only valid Jellicle Choice. The change feels disappointingly petty for the major antagonist, and of all the things that are never explained, the audience is never told why it would be so bad if Macavity did go to the Heavyside Layer. If he’s just going to be reborn, he won’t be any more of a threat than he is now, and at least while he’s growing up he’ll stop being a nuisance.

“Comedic” Characters

I know I listed “music” as part of what was good about the musical, and I stand by that: all of the “serious” songs are pretty good. But every song that’s supposed to be funny, with the surprising exception of “Skimbleshanks the Railway Cat,” is an infuriating combination of cringy and offensive.

While “Mungojerrie and Rumpleteazer” is a cringy, unsuccessful take on a fun and catchy original song, and Rum Tum Tugger is an illogical combination of annoying and lady’s man, the treatment of Jennyanydots and Bustopher Jones is much more concerning. These two are the only two characters in Cats (2019) that are portrayed as heavier, while everyone else, is thin and muscular. To see why this matters, consider the portrayal of the same characters in Cats (1998).

At the beginning of the Gumby Cat Jennyanydot’s song, she’s dressed in an exaggeratedly large costume and lolls around the stage while Munkustrap sings about her lazy daytime activities. Her costume sends a message about the activities being described. She doesn’t move around much during the day, but prefers to sleep, so she’s large, soft, and slow. As soon as Munkustrap starts singing about her highly productive nights spent creating order in the household, she removes her bulky coat. Her secondary costume is a tasseled flapper dress, which not only recalls the active, progressive jazz dancing of the Roaring Twenties, but also caries feminist connotations. The flapper dress is loose-fitting and disguises most of the wearer’s curves, sending the message that outer appearances aren’t of primary importance. The Jennyanydots of Cats (1998) is extremely capable and intelligent, training mice and cockroaches with the efficiency of a general.

The Jennyanydots of Cats (2019) of course can’t have a costume change in accordance with the parts of her personality being shown: the characters are generally nude. While a heavy-set Gumby Cat is still perfectly fitting, the shift in how she’s acted is, frankly, unacceptable. She does loll around the set, as a Gumby Cat should, but she’s incredibly clumsy and undignified. She’s also the only character other than Bustopher Jones, the other larger cat, whose snacking is emphasized during the movie. Jennyanydots is no longer portrayed as an intelligent and capable lady, but is made into an offensive caricature of a fat person. Her only “comedy” is achieved through slapstick clumsiness, mocking the weight of Justopher Jones, and a joke about Rum Tum Tugger having possibly been neutered. Physical humor can certainly have a place in comedy, but not when it’s directed solely at those whose bodies lie outside the “acceptable” norm.

The characterization of Jennyanydots might not be as bad if her portrayal didn’t characterize the treatment of fat characters in the movie. Just like Jennyanydots, the Bustopher Jones of Cats (1998) is dignified and highly respected by the other Jellicle Cats. He’s the classic fat cat and his entire song is about his favorite places to eat, but he’s never once made the butt of a joke for it, either through the way he’s acted or by the other characters. Instead, his weight is a sign of his status. He’s a high-class character that can afford memberships to various clubs that offer fine dining, and his suit and spats – a play on the color pattern of a tuxedo cat – are further reference to his wealth. Bustopher Jones behaves like a gentleman and is treated as one by all of the other cats, who “are all very proud to be nodded or bowed to by Bustopher Jones in white spats.”

The Bustopher Jones of Cats (2019) is, again, made into a caricature. While it matches the song for him to be especially interested in eating, this is made into his only personality attribute, other than an insecurity about his weight that the 1998 character completely lacked. It might be tempting to read his character in terms of a shifted opinion of the rich: instead of his weight signifying his status as a gentleman, it may be indicative of his status as a consumer, in every sense of the word. While it would be wonderful to see class commentary of this sort, the interpretation doesn’t hold water. Bustopher Jones sheds the suit jacket that signifies his class soon after being introduced, and rather than eating the fine dining explicitly named in the song, he eats rotting garbage out of the trash. Even the other characters show obvious disgust with this behavior and with him guzzling a beverage in the middle of singing. There is no reason for him not to have been able to eat politely, at a respectable club (if he had to eat during the song at all – 1998 Bustopher didn’t) since Rum Tum Tugger breaks into a Milk Bar. It isn’t as though the cats in the film can’t get access to reputable businesses, even if the means of accessing them isn’t reputable. They’re cats. The audience will forgive them for breaking and entering.

What Went Wrong?

Even with the best animation or acting in the world, Cats (2019) would have still flopped. What makes Cats (2019) so bad isn’t actually the atrocious visuals – though they’re definitely a huge contributing factor. The worst part of the movie for anyone who liked the original musical is now the remake treated the source material, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats.

Cats (2019) went out of its way to try to make the comedic songs and characters funny by adding slapstick and snarky asides, and it just wasn’t necessary. The musical performances of Cats had very little added dialogue, which meant that the songs (and consequently, Eliot’s poems) were left to speak for themselves. All of the songs were performed with straight-faced but energetic joy, and the perfectly conveyed the humor inherent in the poems themselves. Trying to force the humor through additional dialogue does nothing but detract from the masterfully adapted lyrics.

In addition, in many cases, the added attempts at comedy just don’t hold up with a reading of the poems that heavily inspired the songs. Even when Eliot pokes fun at the cats he’s writing about, there’s always a clear undercurrent of respect for a fellow-creature, and Cats (2019)’s portrayals of the most prominent comedic characters try to achieve humor through mockery.

Considering how little attention Cats (2019) seemed to pay to the lyrics of the songs they took from Weber or the poems in Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, the lesson is clear: creators of all stripes need to do their research. Instead of just mindlessly adapting another adaptation, go back to the original. Understand the choices made in the adaptions that followed to get a better idea of the kinds of alterations that would be best fitted to the present. Not to mention, do some audience tests of your visuals before you commit to horrifying CGI effects.